In its simplest sense deconstruction as an artistic strategy involves breaking an object down into smaller parts. However, at a deeper level Jacques Derrida (Willette, 2014) talks of things (text, institutions, traditions, societies, beliefs and practices) as not having definable meanings and that they always exceed the boundaries they currently occupy. He talks of deconstruction pressing against this and cracking the nut open to disturb the tranquillity and expose what lies inside.

Deconstruction enables us to slice through the history of an object and examine every aspect of it in relation to the world, to the notion of culture and to ourselves. However, much modern art uses deconstruction to create shock value. It forces the viewer to wonder about the purpose, fragility and symbolism of the base ingredients of an object. Deconstruction questions accepted reality as every construction has a history and we cannot hope to understand this history without studying its genesis.

Deconstruction followed by reconstruction mirrors a world that is constantly shifting and evolving in a cycle of life and death. That world imposes on the artist a challenge to respond by integrating fragments of the world around them in new and meaningful forms that are relative to the current environment. We could say that we are carrying out ‘cultural recycling’ by creating new constructions.

The work of British artist Michael Landy, provides a very personal example of deconstruction. In 2001, he took over the defunct C&A department store in Oxford Street. Into this empty concrete shell, Landy installed an industrial processing system and employed a team of uniformed staff to take apart everything he owned, shredding every manifestation of his existence and returning it to dust. Over the following two weeks he deconstructed the 7,227 items inventoried as Landy’s material existence and eventually dumped it as landfill. This deconstruction brings to mind The Origin of the Work of Art by philosopher Martin Heidegger who wrote of the active struggle between ‘earth’ and ‘world’ in art. An artwork is inherently an object of the ‘world’ however the very nature of art also appeals to ‘earth’ as an artwork is made of naturals made from the earth. So Landy’s deconstruction has taken us on a pathway from the world back to the earth and we are left with a perplexing consideration of how and when an artwork becomes art.

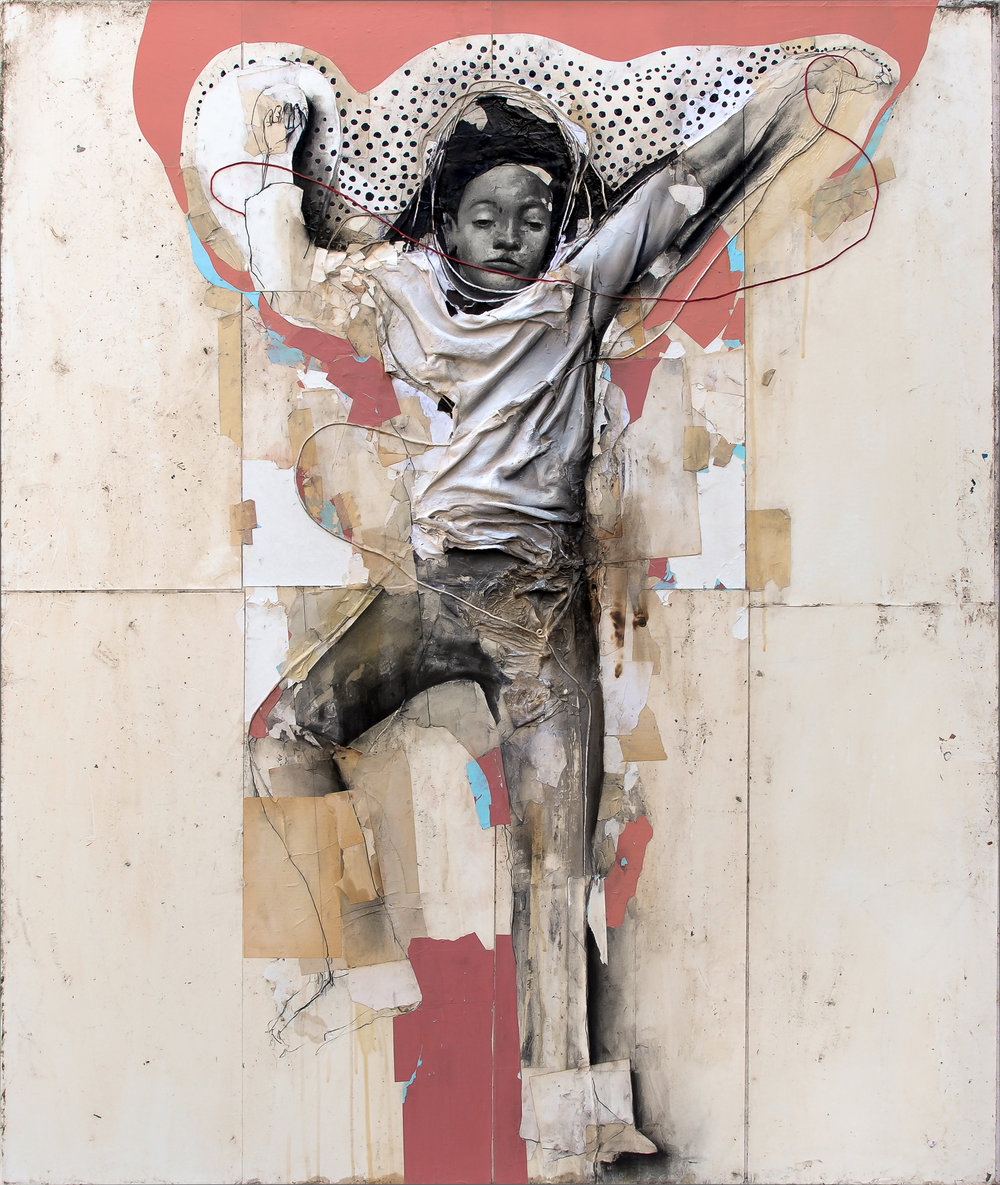

Artist Paul Cristina creates artworks from paper, oil and charcoal on panel. His motivation is to explore ideas of human behaviour that go underneath the familiar exteriors of everyday life. The surface of his works are very physical and intense but they have a hidden congestion of material underneath. He tries to confront that place inside of himself where fear, hate, anger, insecurity and dysfunction reside. He begins with skilfully rendered human figures but cannibalises them by tearing, cutting and distressing. The result is a physical surface that speaks of the ephemeral materiality of our own bodies, on a very visceral level that often shows corpse-like figures. Cristina creates art that expresses things outside of the social norm and we the viewer are able to see something that is too powerful to process in reality.

A very different form of deconstruction is The Third Memory (2000), created by Pierre Huyghe which re-enacts the 1972 hold-up of a Brooklyn bank which was immortalised in the film Dog Day Afternoon (1975). Almost 30 years later, Huyghe provides a platform for the heist’s mastermind, John Wojtowicz, to relate his version of the day in a reconstructed set of the bank. We see Wojtowicz on film talking us through the robbery by referencing footage from the actual event and the Hollywood movie in a confusing mix of real events and distortions of memory. The experience of watching this puts memory itself up for interpretation, it gives what has already happened a second chance.

Looking at these artists in terms of my own work, I particularly like the idea that using memory in an artwork gives the past back its possibility, if not its truth. The way that Pierre Huyghe blurs the past and present and allows a new voice to offer a different interpretation of a past event by commenting on fact and fiction is intriguing.

My experiments to date have focused primarily on deconstruction / reconstruction of a wartime experience from a range of artefacts, but an extra slice of narrative could create a blurred dance between representation and truth that propels the outcome even further. The retelling of the event in a mysterious or even fantastical way could yo-yo between the child and adult, interweaving their stories and each giving their opinions on the other’s version of the truth.

References

Dina, 2015. Fragmentation or deconstruction art? [WWW Document]. That Creative Feeling. URL https://www.thatcreativefeeling.com/fragmentation-deconstruction-art/ (accessed 3.30.20).

How Break Down by Michael Landy Is Subverted in the Digital Age – ELEPHANT [WWW Document], 2018. URL https://elephant.art/break-michael-landy-subverted-digital-age/ (accessed 3.30.20).

Paul Cristina: In Consideration of Mortality [WWW Document], 2018. . Art Aesthetics Magazine. URL https://www.artaesthetics.net/publications/2018/9/6/paul-cristina-in-consideration-of-mortality (accessed 3.30.20).

Pierre Huyghe / The Third Memory [WWW Document], n.d. URL http://www.newmedia-art.org/cgi-bin/show-oeu.asp?ID=150000000035957&lg=GBR (accessed 3.30.20).

The Third Memory, 2000. . Guggenheim. URLhttps://www.guggenheim.org/artwork/10460 (accessed 3.30.20).

Willette, J., 2014. Jacques Derrida and Deconstruction | Art History Unstuffed. URL https://arthistoryunstuffed.com/jacques-derrida-deconstruction/ (accessed 3.30.20).