I carried out another exploration of artists, this time I looked specifically at artists who use any form of baggage in their work as a way to represent memory, the past, loss or travel. I was interested to experience other work to see how an objective experience came across and hence how similar props would relate to the viewer in my work.

Marcel Duchamp’s Boîte-en-valise (Box in a suitcase) below is a portable miniature monograph that includes 69 reproductions of his own work. The box unfolds to reveal pull out standing frames, small versions of his ready mades and loose prints. What we see here is a travelling portfolio and personally I think it’s a very original way to show a set of work. But Duchamp, as we would expect, has a deeper intent as he is addressing the museums’ ever-increasing traffic in reproductions, specifically he is questioning the relative important of the original work of art.

More relevant to my project is his quote below. In this I see how the suitcase is the baggage of life that follows us around, some of it we are proud of and some less so. We can hide some or all of it away or we can let it all spill out as Duchamp has confidently done here. I do like how this case unfurls and we see objects connected together as if feelers are being tentatively put out into the present day – an explosion of the past that has burst open.

“My whole life’s work fits into one suitcase”

Marcel Duchamp

Artist Mona Hatoum presents us with two closed suitcases below and there is something immediately troubling about what we see with human hair connecting them together. When we learn that she had a troubled childhood and was denied Lebanon citizenship then we start to understand. The closed suitcases feel very different to Duchamp’s open one above as here we assume dislocation, exile and constant movement. The hair looks like it is being poured out of one suitcase into the other, as if a child is being torn apart by a separation or a family is being split up. What Hatoum may be referring to is human trafficking and she’s done this by turning an everyday object into something uncanny. The hair could be the threads of a life story that travel from one place to another. What I appreciate about this work is that multiple meanings can be read into it and it is very arresting to look at.

Memory Suitcases (below) is a thought-provoking series by Israeli artist Yuval Yairi that uses old, worn suitcases as canvases for nostalgic landscapes. Like scenes grasped from memory, these propped up travelling cases feature a range of sepia-toned settings. The series presents the objects as though they are relics of a civilization long forgotten, each with their own story to tell.

I get a sense of sentimentality when I look at the work, that the artist is relating a positive experience from their younger life. It tells a number of stories of leaving one lifestyle for another, with the suitcase holding rose tinted memories from a life altering journey. Most interestingly, what we see is mimicking the natural process of memory in how we remember scenes but the detail of an experience is locked away deep inside us.

Mohamad Hafez (below) is a Syrian artist who creates intricate and harrowing miniature dioramas of war torn Syria. the level of detail in his work is astounding as we can see a car covered with dust, debris scattered around and even a pair of child’s shoes and destroyed toys. The whole scene is exploding from a open suitcase and asks questions about the ongoing refugee crisis by recreating the homes that 10 refugee families were forced to leave behind.

Hafez’s work shows what only art can do in such horrific circumstances as it creates a neutral platform to engage with us without us having to open our mouths. He is simply telling us 10 stories through art and he is using the ‘baggage’ that these poor people are left with when all around them is lost. The exhibits are accompanied with an audio recording so viewers can listen to the actual refugees telling their own stories. Most potently, many of the suitcases were donated by Jewish families, who had been given them by their grandparents who escaped persecution in Europe during WW2.

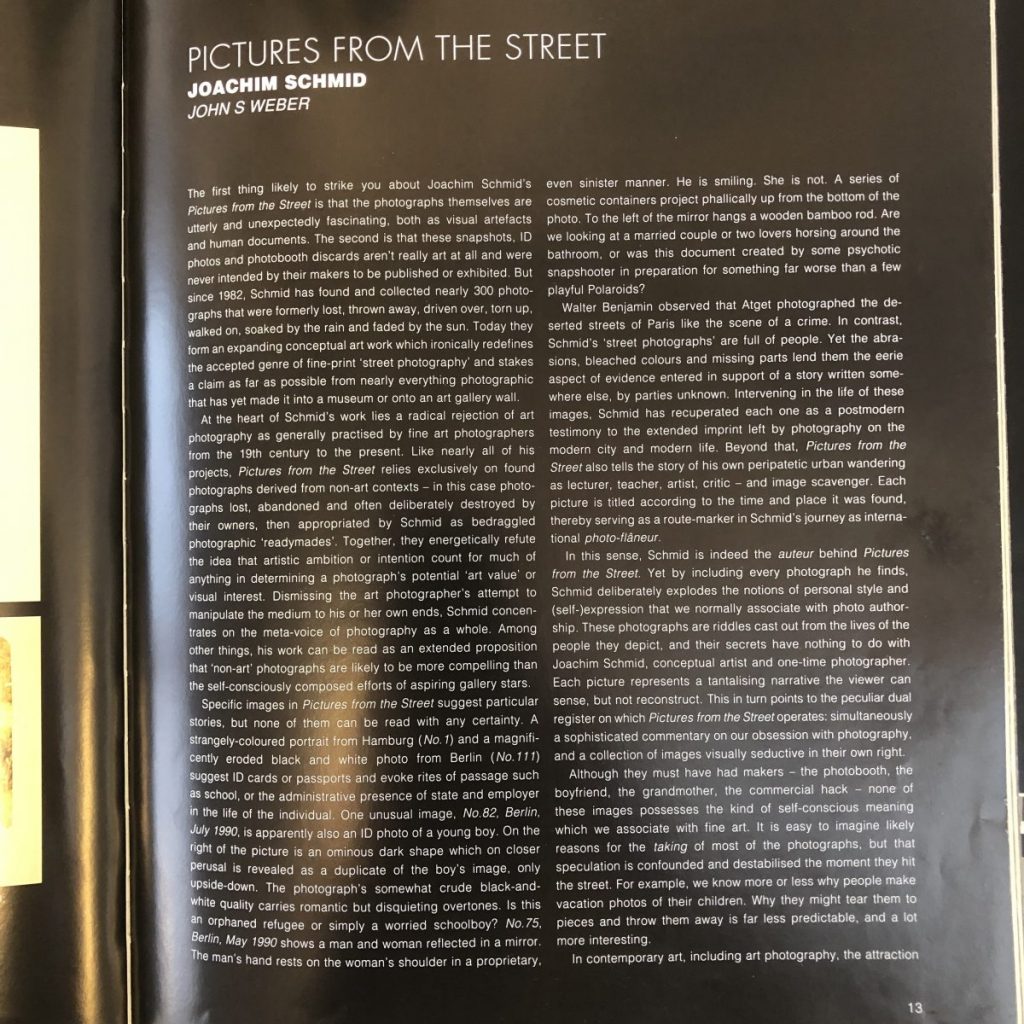

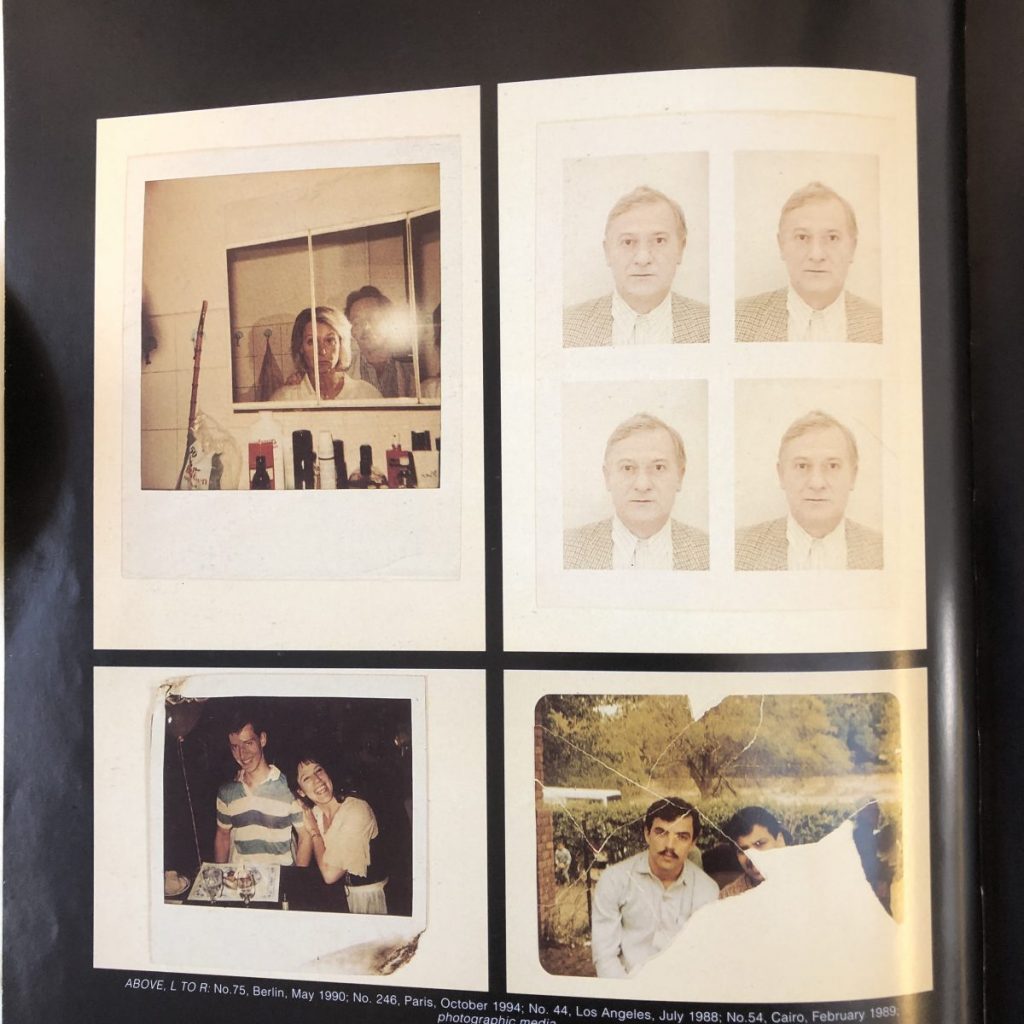

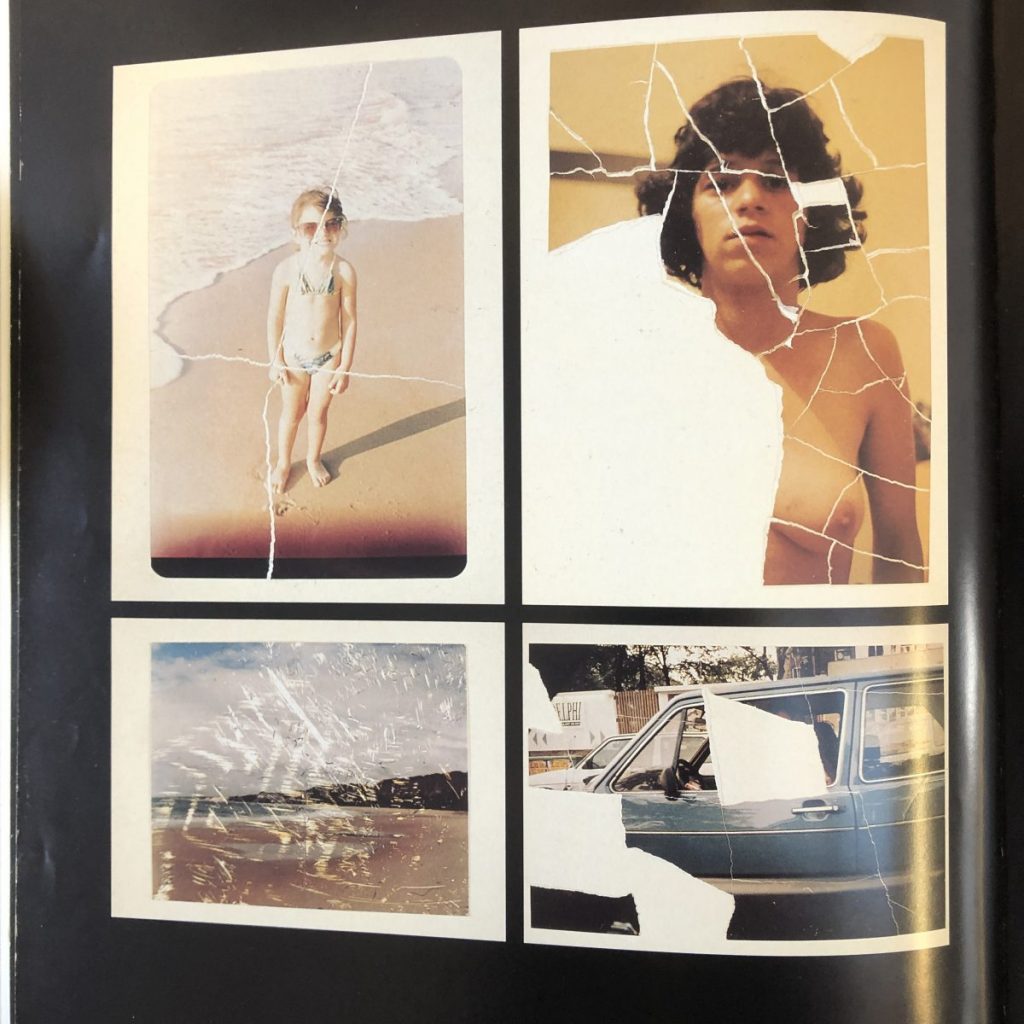

Finally, I came across the work of Berlin-based critic and conceptual artist Joachim Schmid in a journal and it drew my attention in how he collects and reuses photographs that others throw away. This is not bound in a suitcase but it is personal baggage all the same – hence I thought it very relevant. The visual poetry he creates from torn up photos, mundane scenes and discarded mistakes is very alluring. Schmid particularly revels in collecting photos that people throw away in public, especially if they have been discarded with some animosity or intense feeling.

This curator of photographs is acting like a modern day anthropologist in trying to understand our culture by what we have left behind. This is a novel way of curating a collection based on what we have rejected from our lives, not what we want to carry with us. As a viewer we cannot escape from our curiosity of wanting to know why each photo was thrown away and what memory each one contains.

Summary

The artists above have used baggage in many forms as a prop or container to present their work. It’s remarkable how each work creates its own viewer experience based on how the baggage has been used. From Duchamp’s closet of treasured work to Hafez’s shocking Syrian homes, we see how the container can represent a set of stored memories or indicate a state of unrest and upheaval.

How does this fit in with presenting my own work? ‘I Know About the Horses’ represents a set of memories, specifically spoken words, that I have subverted in my own mind over time. I still carry some of the baggage that they carry with them but I have moved on and it’s important to show that I have dealt with what ever this language was originally meant to represent. Saying that, there is a small element of loss which I’d like to give a hint of, but not too much.

My suitcase representation with clothing and scattered postcards is still working well based on what I’ve learnt above as the case gives both a sense of vague memory and subtle loss. But I’m also interested in how Schmid includes torn photographs above as this is symbolic of a violent decision and a keenness to forget. On that, I’ll continue to experiment with both how the postcards are shown but also the physical positioning of the cases in a space – be that on the floor, on plinths or on a well as each of these throws up extra interpretations.